What’s LUFS Got to Do With It? – Part 1

If you’re doing any kind of broadcasting whether it’s online streaming, delivering for TV, or even just uploading content to the web, this one’s for you.

If you’ve been looking around the web and forums at all things audio or if you’ve been doing anything for TV, you might have seen some talk about loudness metering along with terms like LUFS or LKFS show up in discussions regarding levels and loudness for broadcasting. You might have even seen these show up in recent articles relating to YouTube, Spotify, and the Loudness Wars.

So what exactly are LKFS and LUFS?

These are units of measurement pertaining to loudness measurement, but we’re not talking in terms of SPL like we might measure within a performance space. These are units of measurement pertaining to the perceived loudness of an audio signal.

Wait, don’t our existing meters already do that?

Nope. I could probably do several articles on the various forms of metering out there, but I’m going to keep this very simple for now. Traditional audio meters were really just designed to get levels set to optimize the signal to noise ratio and avoid more distortion than necessary. It is only with the modern loudness meters that have entered the market over the last 5-10’ish years that we can take an audio signal and get a very good idea of the perceptual loudness of the signal.

But why do we need a special meter to measure loudness?

Basically, it’s because our hearing isn’t linear. If we toggle between a 100 Hz sine wave, a 1 kHz sine wave, and a 10 kHz sine wave at the same signal level, we will not hear them as the same loudness because of the principle of Equal Loudness which I’ve written about in the past. Why we need a loudness meter now when we’ve never had them in the past is something I’ll get to in a bit, but let’s get back to LUFS.

LUFS stands for Loudness Units below Full Scale. LKFS stands for Loudness, K-weighted, relative to Full Scale. LKFS and LUFS are exactly the same thing. Most of the world uses LUFS while American broadcasters uses LKFS because…well…’Merica!

All you need to know right now, though, is they’re the same thing. Anytime you see LKFS you can substitute LUFS and vice-versa. I’ll use LKFS When I’m talking about stuff where the documents you might see would use LKFS, but otherwise I’ll use LUFS because it’s what most of the rest of the world is using.

So what’s a “Loudness Unit”?

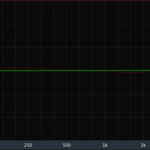

Several years ago, a new manner of measuring loudness was established courtesy of ITU 1770. ITU 1770 was originally published in 2006, and I picked up on it a few years later as the first loudness meters began coming to the market. I’m going to simplify this quite a bit, but a loudness meter employs an algorithm using a filter to create a weighted measurement of an audio signal. There’s obviously a bit more to it especially when you start adding in surround sound formats, but this is a good place to start. If you’re familiar with SPL measurement weightings such as A-weighted slow, the concept is quite similar. In this case, the filter is designed to help replicate where our hearing is the most sensitive and is known as K-Weighting.

So our “Loudness Unit” or LUFS or LKFS is basically the unit of measurement we read on our loudness meter. It is still a “dB”, but we use LUFS or LKFS to denote it was measured with a loudness meter. If you want to find out more about the measurement algorithm, you can check out ITU 1770-4 for yourself.

What you really need to understand about all this, though, is LKFS is the current standard for audio levels when delivering broadcast audio, and the use of loudness metering is in the process of integrating into all facets of audio production including music production. If you’re not currently using some form of loudness metering for your broadcasts and audio related products, let’s look at why you should start sooner rather than later.

As the audio industry really began to embrace digital audio in the mid and early 90’s when CD’s became the most popular format for music, a tendency developed to push signal levels of our final products right up to the limit of 0 dBFS for a variety of reasons I’m not going to start ranting about today.

The typical workflow was to stick a limiter at the end of the signal chain and push the level up until the signal level was high as it could go. The problem with this, though, is it only addresses signal peaks, and we don’t judge loudness based purely on peaks. The result of this practice is audio media over the last 20 years has endured a varying degree of perceived loudness across content because content with a very small amount of dynamic range(lower peaks) would be pushed to a higher signal level than programing with a wider dynamic range.

This is what enabled the Loudness War. Engineers would limit their peaks in order to push their average(RMS) levels closer to 0 so a song or commercial or television program with a smaller peak to average ratio would come across as louder than something with a larger peak to average ratio. I’ve written in the past about how easily we can be deceived into thinking louder things are better, and the misguided loudness war thinking was if your program or song is louder people will think it sounds better and pay more attention. In some cases, this can be true, however, the loudness wars pushed things to an absurd level and audio quality suffered in the process.

TV commercials especially pushed this for years to grab the audience’s attention, but it ultimately didn’t work because people hate commercials. So they just turned down their TV’s and complained until the government finally said enough is enough and passed the CALM act mandating that commercials can’t be louder than the TV program itself.

This loudness war problem is a big part of why loudness metering now exists. Using loudness metering allows us to mix to a fixed perceived Loudness so that all content will come across as being at relatively the same volume when played back to back.

In the world of television this means every show and advertisement on a station can be the same loudness. In the world of music, every song played back to back can be the same loudness. On the internet, jumping from one video to the next will put them all at the same loudness.

It’s a wonderful thing for the consumer because they don’t need to chase how loud things are with their volume control. They can simply set their volume to their preferred level and sit back and consume. Delivery platforms like YouTube and Spotify know this and employ Loudness Normalization to move everything to the same loudness level. It’s also a wonderful thing for audio engineers because we no longer have to worry about reducing our transients.

The key thing to understand today, though, is Loudness Metering helps us create consistency. When you begin outputting all of your audio content from podcasts to web streams to videos with a standardized loudness level, you will begin creating a consistent volume for your programming.

In my next article I’ll get into more of the specifics of using a loudness meter and offer some suggestions for workflow and a target level based on what’s going on in the industry right now.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post