Going Wide, Again

Let’s talk EQ filters again. About a year ago I wrote a post about classic EQ’s and how wide those filters tend to be; for those who missed it, classic EQ filters are usually pretty wide. However, I have a feeling a lot of people missed that one because I still come across a lot of guys doing these spiky, little jabs all over the place with their EQ’s, and I don’t get it.

OK, maybe I do get it. At some point someone said the general “rule” of EQ is to cut narrow and boost wide. The motivation behind the cut narrow part is to not remove any more than necessary from a sound, and I’ll agree with that. But shouldn’t that go without saying? Why would you ever want to do more than you need to with any sort of processing?

My problem with that “rule” is that it doesn’t provide any context on what narrow means. So I see a lot of educated audio folks following the “rule” who go for these extremely sharp cuts for all of their EQ’ing. And when I say “narrow”, I’m talking about EQ’s that are 1/3 octave or less in width, and usually they’re less.

I’ll admit there are times when the quickest and even best solution is a very narrow, deep surgical stab with an EQ. That’s often the best way to fix a strange ring or resonance that can’t be dealt with at the source. But you shouldn’t have to do that on every input.

Last time I addressed this idea, I talked about classic EQ’s and their wider filters. For now, let’s forget those romantic, classic EQ’s everybody loves and holds up as the standard, and look at our microphones.

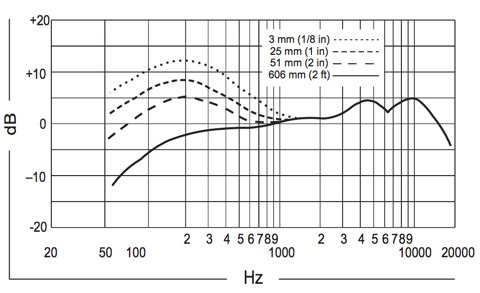

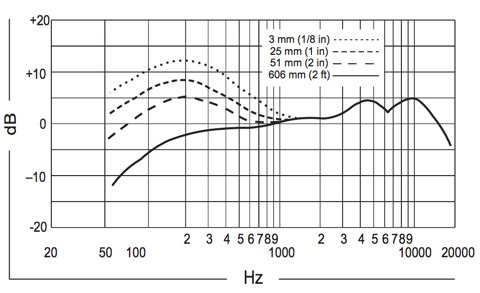

Shure Beta58A Frequency Response

The image above is the frequency response of the popular Shure Beta 58A direct from Shure’s spec sheet. I know some guys don’t exactly understand how to read these things so let’s look at what this response means.

Take a look at the solid line in the graph. This line represents the frequency response of the microphone at a specified distance. The best way to understand this is the frequency response is the EQ curve the microphone applies to a sound source at that specified distance.

If we follow the Beta 58A’s response displayed here, we can see that the microphone’s frequency response below 1000 Hz is down a bit but still fairly smooth and starts rolling off below 200-250 Hz. Above 1000Hz, the mic boosts the upper-mid and high frequencies a bit with a 5dB boost around 3.5/4 kHz and then another 5 dB boost centered around 10 kHz. Each of these boosts looks to me to be approximately an octave wide. These boosts can give a vocal a nice bump in the presence range and are part of why the Beta 58A has been a popular vocal mic through the years.

Of course, the thing you need to understand about the solid line on the frequency response is that it was measured for a sound source placed 2 feet away from the mic. When’s the last time you heard an effective live vocal sung into a Beta 58A that was 2 feet away?

Fortunately, Shure provides us with information on how the Beta58’s frequency response changes when we place it in a real world situation.

Take a look at the dashed lines in the graph. Each one represents the frequency response of the microphone at a different distance to the source. That bump you see centered around 200 Hz that increases as we move closer to the microphone is called Proximity Effect. All directional microphones exhibit proximity effect, however, the amount and frequency range affected varies between different mic models.

On this particular microphone, our proximity effect bump happens to be right in the middle of the Mud Range. At 1/8″ with our singer kissing the mic, we get about a 12-13 dB boost at 200 Hz which can have a tendency to muddy up a vocal. This would be one reason why some engineers do not care for the Beta58 as a vocal mic.

But I’m not talking about the pro’s and con’s of different vocal microphones today. I’m talking about why you should probably be using wider EQ filters.

Take a look at that proximity effect in the graph again. What do you know? That proximity effect is about 2 octaves WIDE. So if you were going to compensate for this with an EQ, do you think you’d get the best results from using a narrow filter or a wide filter?

I know the next question: what do you do about something that just doesn’t sound good?

Call me old fashioned, but that’s not what EQ is for. If the source isn’t any good, you fix the source. Not everybody on this planet was meant to be a singer, guitarist, bassist, trumpet player, violinist, bag piper, etc. In similar fashion, not all instruments were made to be heard outside of a bedroom, basement, or garage. Fix the source.

So what about EQ’ing? Dave Rat has talked a bit about his approach to channel EQ, and it’s pretty simple and probably a good place for most engineers to start in their EQ journeys.

Dave Rat uses his channel EQ’s to adjust for the combination of the sound source AND the microphone. In other words, you take a source sounding the way it’s supposed to, put a microphone on it, and then make any necessary adjustments with channel EQ due to the microphone and source interaction to achieve a desired tonal balance through the PA. In a perfect world with an unlimited mic locker, you might just opt to change out the microphone altogether for something that’s a better fit before even going to EQ.

Look at that frequency response one more time. If we need to correct for any of the things this microphone does to our vocalist when he kisses the mic, a narrow filter won’t be enough. The bumps in the upper-mids and high frequencies are about an octave wide and the proximity effect is much wider than that. If we need to make adjustments due to our microphone and vocal interaction, we’re going to need a wide filter(s).

This is just some stuff to think about the next time you’re reaching for the Q knob on your EQ. Narrow EQ’s aren’t always a bad thing. If you have no choice but to resort to an EQ to fix a strange ring or resonance on an instrument, a narrower, surgical EQ cut might be just the trick. But if you’re doing more general EQ work like cleaning the mud up on an instrument, my guess is you’ll get better results if you start thinking about using a wider EQ(think in the neighborhood of 1 octave) for most of your EQ’ing. Just remember: always USE YOUR EARS as the final judge.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post

Every filter introduces phase distortion (okay, FIR filters are different). More filters used means more phase distortion. Therefore, when multiple filters fall close together spectrally, it usually sounds “better” when the filters are replaced by a single wide filter.

I think it really comes down to just doing what is approptiate. “Use your ears” as you say, rather than doing something becuase you read somewhere that this is how you should do it. =D

Getting a better source is great, but not always realistic in smaller churches. What I do is make a point of letting leadership know if the musicianship was beneficial to the sound, and I don’t mention it if it wasn’t. 🙂

It’s worth taking note of any EQ you find yourself doing on a regular basis, or anything drastic. If you’re always taking 300Hz out of your vocals, it’s worth trying a mic that has less of it. On a similar note, I had an SM57 on a last minute Djembe and once I’d got it sounding decent the EQ curve resembled the response of an E602-II, so that’s what I used the next time. 🙂

Chris